Menstruation as Muse

Representation of the bloody is nothing new in art. The bleeding subject has been present throughout the history of artistic expression; representing heroism, sacrifice, tragedy; all through a flick of red paint on the canvas. However, one bleeding subject has traditionally been excluded from this. Despite being the literal lifeblood of our civilisation, menstruation is eerily absent from most of art history. The violence and gore of battle are commonplace, but what renaissance nude pictures a menstruating muse? This absence reflects a societal rejection of the menstruator, which still looms large and dull over contemporary culture. A lack of visual representation renders period blood ‘taboo’, promoting fear and disgust, and from this, cultural stigma and exclusionary practices that literally shut out and silence the menstruator.

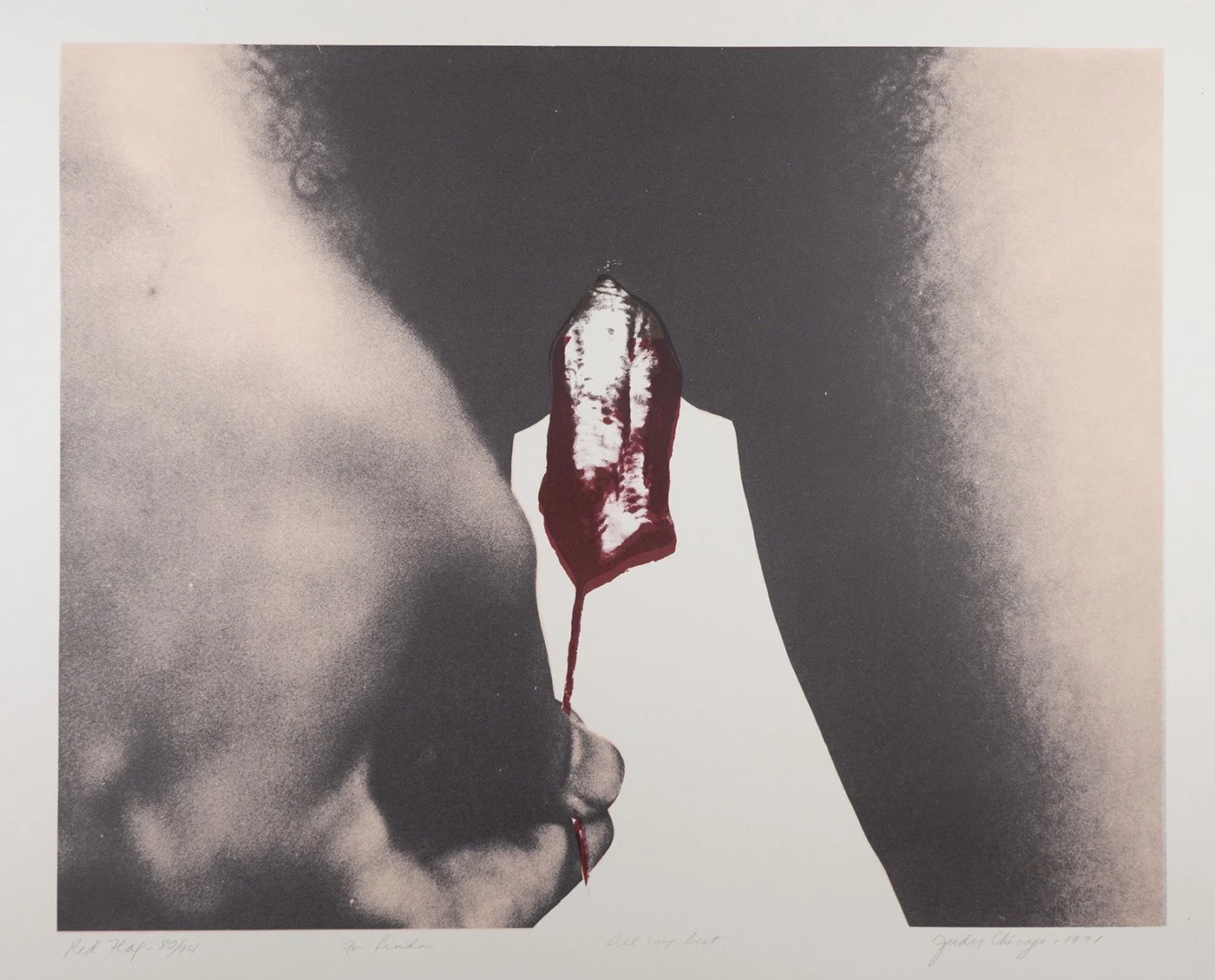

‘Menstrual art’ eventually took off alongside the feminist movements of the 1970s. Judy Chicago’s iconic ‘Red Flag’, a photolithograph depicting a subject removing a bloodied tampon, exemplified a new feminist focus on revealing a ‘bloody’, bodily truth. This forced onlookers to confront their own reactions to this visual. Why is this so provoking, and why is it still so provoking to menstruators when it is so instantly recognisable? Images like this help to unravel both cultural and internalised shame. This bold exposition also has a similar effect to naming ‘He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named’; undermining the terrible, mysterious power of a period, and naturalising it through representation. Afterall, leaking isn’t so horrifying once you’ve been confronted with the glory and pride of this image.

Judy Chicago Red Flag 1971

Chicago’s piece played an essential part in the wider menstrual movement of this time, undeniably fuelling further period activism by creating an icon, and a conversation starter. This work was situated within a fever of artistry that sought to expose the totality of the menstrual experience. Leslie Labowitz-Starus and her performance art piece ‘Menstrual Wait’ emphasized the mental toll of waiting for a period. Although today discussion of such things is commonplace, at the time this was so outrageous that she was almost expelled from the Otis Art Institute of LA, underlining the fact that the mental health of menstruators is also wrapped up in this insidious web of shame, and silence. Other artists tackled taboo through the use of actual menstrual blood. Vanessa Tiegs and her series ‘Menstrala’ painted soft, swirling images in menstrual blood, radically embracing this as a source of beauty, and spiritual power, rather than abjection.

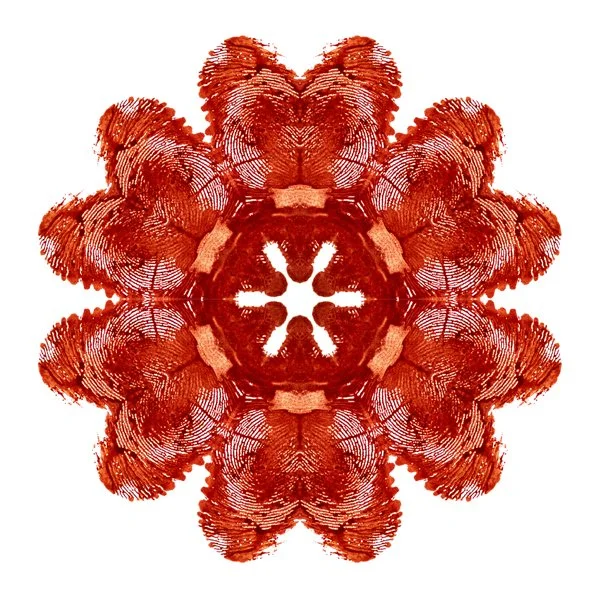

The menstrual art movement has developed further in recent years. These earlier works were largely from a second-wave feminist perspective, meaning predominantly white, western, and highly gendered. This has rightly evolved. Zanele Muholi’s series ‘Isilumo siyaluma’, consists of flowers printed in menstrual blood, exploring the curative rape black lesbians face in South Africa. The use of blood has moved away from Tieg’s emphasis on reclaiming its beauty, to embodying the violence of patriarchal rejection, and its traumatic consequences. The visceral quality of these images confronts the viewer with the raw pain of its subject matter; drawing them into the human truth of this narrative.

Zanele Muholi Isilumo Siyaluma 2011

Poulomi Basu is another artist who represents a new generation exploring menstrual art. Her photographic series ‘Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile’ exposes the Hindu practice of Chhaupadi which banishes menstruators from their homes during their period. This is a practice that not only positions menstruators as dirty, and sinful, but also leaves them vulnerable to the natural elements, and sexual violence, resulting in several deaths. ‘Blood Speaks’ is a multimedia project, which uses virtual reality films, photographs, projections, and a soundscape to create a totally immersive experience for the viewer, allowing them a powerful insight into the feeling of this practice. The isolating effects of this are effectively portrayed through both the intimate images of these menstruators photographed alone, as well as the use of a virtual reality headset, forcing the audience to confront this sense that they are removed from a shared space, separated from family, friends, and their home. This is intersectional work that reflects an increasingly intersectional movement, moving beyond the initial bold visual statements that defined earlier menstrual art, to look instead at how art can be used today to represent and fuel change globally.

Poulomi Basu Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile 2016

I have written this blog today to not only explore the history and significance of menstrual art, but to also introduce a new creative project at Sanitree. We are hoping to start a shared creative space which will explore the theme of menstrual art through your submissions. This could be through whatever medium you choose; paint, photography, poetry, prose; or anything that inspires. Menstruation is teeming with a wealth of meaning, and creative potential, and exploring this, and reclaiming this space is crucial to undermining the stigma, and shame that comes from silencing this experience. Additionally, every menstruator is different, and we would love to empower these differences, embracing the individual bleeder, and their individual experience.

Please email your submissions to: sanitree.scotland@gmail.com